Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O'Keeffe

From the Introduction to Full Bloom:

Georgia O'Keeffe may be the best known and least understood artist of the twentieth century. She was a woman who lived the newspaper editor's adage that, if the myth is more stirring than the truth, print the myth. Nonetheless, I have attempted an honest portrayal of the woman behind the myth, exploring her remarkable strengths and talents as well as the demons and dark past that occasionally drove her to behave cruelly.

When I began this book a decade ago, I had not yet interviewed the dozens of people who knew O'Keeffe, nor read the thousands of letters from her and about her. In the course of my research, a woman emerged who was confident and troubled. I reevaluated the suppositions of previous biographers to discover a woman who, contrary to general opinion, was not born with naturally fierce independence and indomitable creativity. In fact, O'Keeffe's story turned out to be characterized by great suffering, professional and emotional set-back, and by good fortune and the wisdom to take advantage of it. O'Keeffe, like many great artists, was not thrilled with the truth of her own story and took pains to disguise her past.

In her idealized autobiography, Georgia O'Keeffe, she described her early childhood on a Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, farm as idyllic. The truth is that her parents were not happily married and bad decisions made by her father proved to be disastrous to the welfare of the family. Her father lost the substantial fortune built up by his parents and his in-laws. As a result, shortly after the turn of the century, when families were less migratory than today, O'Keeffe was forced to move three times during high school; these moves were followed by studies at two colleges in different states. The combination of such geographical upheaval and her family's loss of income left her in Chicago, at the age of twenty, with little hope of becoming an artist. Instead, she worked long hours as a freelance illustrator for miniscule pay.

Scattered dreams, piecemeal education and poverty; this is not the picture painted in O'Keeffe's own autobiography.

A debilitating case of the measles forced the adult O'Keeffe to move back to Charlottesville, Virginia, to live with her sisters and mother. After her recovery, while taking classes at the University of Virginia, O'Keeffe learned the theories of artist and teacher Arthur Wesley Dow. His philosophy of design, that art should consist of filling space in a beautiful way, had a two-fold effect. It introduced her to a method of abstraction within decoration that became the basis of her most successful paintings and re-animated her desire to pursue teaching as vocation.

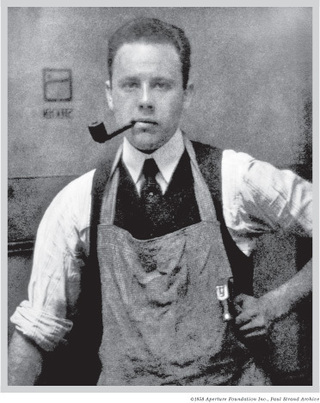

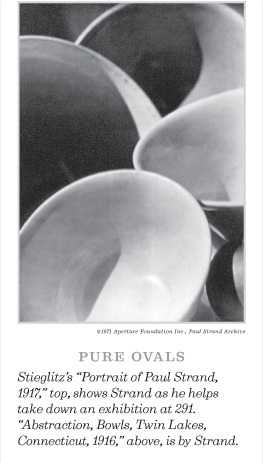

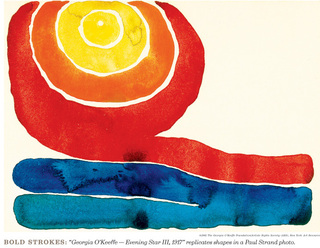

Over the next five years, O'Keeffe developed her first abstractions, which were shown at Alfred Stieglitz' modern art gallery, 291, where Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were first presented in the United States. Her relationship with Stieglitz during these years was professional. She was infatuated with Paul Strand, the young photographer who was Stieglitz' most promising protege. Strand's cropped and close-up style of photography was crucial to the development of O'Keeffe's painting.

Photography, combined with Dow's theories, enabled O'Keeffe to develop a style of painting that was rooted in realism yet abstracted by virtue of the foreshortening and cropping borrowed from the lens and the darkroom. In the early twentieth century, painting largely remained the preserve of men; photography was a relatively fresh field of endeavor in which women were allotted recognition, even sales. O'Keeffe insinuated the graphic power of photography into her painting, thereby finding unprecedented acceptance in the closed world of fine art.

Strand traveled to Texas and brought O'Keeffe, suffering from influenza, back to New York. When faced with the financial responsibility of caring for her, however, he surrendered the field to the well-to-do Stieglitz.

O'Keeffe had enjoyed a lively correspondence with Stieglitz and saw him as a source of stability. Unfulfilled by his marriage of nearly twenty-five years, Stieglitz saw an impressionable woman who needed his help. Within weeks of her arrival in New York, Stieglitz, 54, left his wife to live with O'Keeffe. O'Keeffe, 31, blossomed under his attention. His photographs of her are considered iconic proof of their passion. With his help, over the course of the next decade, she became the most famous and highly paid woman artist in the world. She also became less accepting of all that Stieglitz did and said. In 1927, three years after Stieglitz married O'Keeffe, she was at the peak of her creative power, making the large scale flower paintings that now stand as masterpieces of American modern art. At the point when O'Keeffe was enjoying her independence and generating most of their income, Stieglitz lost interest in his creation. He needed another ingenue to impress and began an affair with Dorothy Norman, a wealthy married woman of twenty-one, seven years younger than his only daughter, Kitty.

O'Keeffe, heartbroken, endured their open love affair until 1933, when she suffered a nervous breakdown that left her hospitalized for two months. Afterwards, she sought solace in her art and in time alone in New Mexico. The wound would not heal since Norman continued to work closely with Stieglitz at An America Place, his third art gallery, until his death in 1946.

I had the good fortune to interview Dorothy Norman. Having read the correspondence between Stieglitz and Norman, it is clear to me that he considered his relationship with Norman to be crucial. Certainly, he refused to deny it, even as it destroyed his relationship with O'Keeffe. It was Stieglitz' emotional and sexual infidelity that drove O'Keeffe to redefine herself, not as he saw her but as she saw herself, in New Mexico.

After making her permanent move to the Abiquiu in 1949, O'Keeffe was the subject of a Vogue feature story with photographs taken by Cecil Beaton. Ansel Adams, Todd Webb and Arnold Newman are just of few who also took her portrait, a proliferation that helped her erase the pictures of herself created by Stieglitz. Today, few conjure a mental image of the slender young woman photographed by her elderly lover, Stieglitz. Instead, we see O'Keeffe as she saw herself and as she presented herself to others: noble, aloof, wrinkled from sun and hard work, long hair covered in a black turban, posed with her bleached skulls in an adobe house.

In the end, she controlled her own destiny. Yet, she grew lonely, especially after her eyesight began to fail when she was in her eighties. She acted in ways that can only be called callous, hurting many of her closest friends. O'Keeffe's last meaningful relationship was with a young sculptor, Juan Hamilton, whom she considered a friend and employee. When O'Keeffe died in 1986, at age ninety-nine, he inherited the bulk of her estate.

Hopefully, this biography, which contains quotations from letters and interviews never before published, will add to the understanding of the woman rather than further the myth.

Read an excerpt from Full Bloom printed in The Los Angeles Times, August 22, 2004.